Student loan | Federal <b>Student Loan</b> Debt Exceeds $1T; $103 Billion in Default <b>...</b> |

- Federal <b>Student Loan</b> Debt Exceeds $1T; $103 Billion in Default <b>...</b>

- Budget Buster: Take your sweet time on <b>student loan</b> payments <b>...</b>

- <b>Student</b>-<b>loan</b> FAQ: What happened July 1, and what comes next <b>...</b>

- No Barriers program helps decrease <b>student loans</b> by more than half <b>...</b>

- We Have a Massive <b>Student Loan</b> Forgiveness Program—Why Is It <b>...</b>

- The <b>student loan</b> crisis hurts for-profit and community college <b>...</b>

| Federal <b>Student Loan</b> Debt Exceeds $1T; $103 Billion in Default <b>...</b> Posted: 21 Sep 2015 12:10 PM PDT Public Service Loan Forgiveness program up six fold in two years | ||||||||||||||||||

| Budget Buster: Take your sweet time on <b>student loan</b> payments <b>...</b> Posted: 20 Sep 2015 10:00 AM PDT ANDREAS RENTZ/GETTY-IMAGES Three cheers for the blatant election bribe that made student loans interest-free for domestic borrowers. Of the 10 milestones of financial success, there's one that's extra special. Being totally debt-free is a helluva achievement, but one I couldn't quite tick off the list. It was the dreaded student loan that brought me low. While university days are already a distant memory, the debt lingers on and on. Psychologically, it would be nice to get it off my back once and for all. But financially, I'm enjoying paying it back as slowly as I possibly can. I can already sense the first bubbles of rage-spit forming. Keyboard warriors, limber up both your typing fingers. There's a controversial opinion coming your way. The best way to tackle your student loan debt is to do absolutely nothing at all. Let it get slowly sucked out of your pay at the minimum rate, bit by bit. It's all automatic. There are two forces at work here, the first being inflation. Every year, the value of all our money shrinks a little bit, meaning prices go up and we can't buy as much stuff with the same fiver. Inflation also shrinks the 'real' burden of any debts you owe. On any normal loan, the interest rate charged means the lender more than compensates for the ravages of inflation- usually 10 times over. But being interest-free, student loan debt is unique. For once, inflation becomes your best mate. Every year, it nibbles away a little more of your debt. READ MORE BUDGET BUSTERS: That would be reason enough to dawdle, but there's another half to the double-whammy. If you repaid your student debt immediately, that money is gone forever. What could you have done with it in the meanwhile? This is called the 'opportunity cost'. Let's say you wipe out a $20,000 student debt within your first couple of years in the workforce. At the minimum repayment rate, it would have taken about eight years to drain out of your pay packet, depending on your income. Over that time period, you could have either used the savings to pay down other debt, or invest. Either way, your original $20,000 would be worth a cool $30,000 or more. Every extra dollar you repay is a dollar that could have been put to work. There's one very important warning here, which goes out to those with itchy feet. If you wander off overseas, interest will start piling up again. That means those who have plans for a big OE or a new life abroad may want to take an aggressive approach to clearing the ledger before they leave. Some expats have taken the opposite strategy, and haven't paid back a cent. It might have saved them in the short-term, but they now face possible arrest at the border. My sympathy is limited. They broke their social contract. Some people would argue it's also your civic duty to repay your loan as fast as possible, rather than taking taxpayers for a ride. Presumably these holier-than-thou types refuse every benefit and credit they're entitled to, and write the Inland Revenue Department a generous bonus cheque on top of their tax bill each year. All you have to do is what you're required, which means repaying the loan. Anything else is essentially a donation, and personally, filling the Government coffers is bottom of the list of causes I'd support. This might be the first column I've ever written encouraging people to keep sitting on their butts and embracing the status quo. So pull up a La-Z-Boy, and reach for the potato chips. If you've done nothing, you've earned it. - Stuff | ||||||||||||||||||

| <b>Student</b>-<b>loan</b> FAQ: What happened July 1, and what comes next <b>...</b> Posted: 08 Jul 2013 07:52 AM PDT Hey MinnPost, I've been trying to keep up with news reports about student loans, but all I really understand is that Congress failed to act and on July 1 interest rates doubled. Does anybody have an idea how much this will cost Minnesota students and their parents? Are college-bound 2013 high-school grads just exceptionally unlucky or can this be fixed? — Debtor to be Dear Debtor, Of course you're confused. We're talking about a minimum of five different kinds of loans and seven proposals for establishing interest rates. And like so many things financial, trying to compare the details can feel like a game of three-card Monte. Making matters worse, these days the colleges where students tend to take out the highest loans are owned by for-profit corporations, which means you can't necessarily do what some of us did back in the good old days and turn yourself over to your friendly local student aid adviser. Think of what happened July 1 as a miniature fiscal cliff. Having failed to agree about pretty much anything, Congress has kicked the can down the road a couple of times on student aid. Last week lawmakers failed to kick it one last time, with the result that the time-buying compromise of years past expired. On July 1, interest rates doubled from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent on subsidized Stafford loans, which are for mostly undergraduate students whose low-income families cannot afford their college costs. Recipients may borrow $3,500 as freshmen, $4,500 as sophomores and $5,500 a year thereafter up to a cap of $23,000.

Source: U.S. Department of Education Notes:

The subsidy: The federal government pays the interest on the loan while the student is in school and in certain other limited circumstances. On June 30, unsubsidized Staffords had an interest rate of 6.8 percent, which did not change. They are also capped, but may be extended to students who are not from low-income families. Most students who are eligible for the subsidized loans end up with unsubsidized ones, too. Nor did the 7.9 percent interest rates change on PLUS loans, uncapped loans that can be taken out by graduate and professional students and by the parents of undergrads with good credit. Also unchanged for now are terms on Perkins loans, for students with "exceptional need," and on consolidation loans made to former students with several loans to pay off. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 55 percent of new loans this year are unsubsidized Staffords worth $59 billion. Subsidized Staffords account for 26 percent, or $28 billion, and PLUS loans 18 percent, or $19 billion. Perkins loans account for less than 1 percent of government student loans. Rates apply only to new loansThese rates apply only to new loans — in other words you, Debtor to be, not your kin who are struggling to pay back past loans. Hold on a second — I'm trying to figure out whether I can afford to start school in eight short weeks, not whether the Wharton School MBA person needs to understand this stuff was a good investment. What does this mean for my wallet? --Indebted for any Enlightenment Congress can still act in time to change the picture for this fall; whether it will is another question. This week, Senate Democrats are expected to take a vote on whether to retroactively freeze new subsidized Stafford loans at 3.4 percent for one more year, for example. However, Republicans have reportedly vowed to filibuster such a plan. Most experts seem to think that if corrective action of some kind isn't agreed to by the August recess, the July 1 changes will affect students taking out subsidized Stafford loans now. Make no mistake, without action the indebtedness in question will make your wallet lighter indeed. According to a recent report from the Minnesota Office of Higher Education, the state's 2010 graduates owe an average of $29,800. Graduates of the aforementioned for-profits owe an average of $41,500. These averages include students who never finish college as well as those who complete only inexpensive two-year programs at public community colleges. Getting a four-year degree or beyond can run up that debt load considerably. "According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, almost 13 percent of student-loan borrowers of all ages owe more than $50,000, and nearly 4 percent owe more than $100,000," Minnesota 2020 Hindsight Community Fellow Ronald Goldser writes. "Economist Joseph Stiglitz notes that approximately 17 percent of student-loan borrowers were 90 days or more behind in payments at the end of 2012. If student loan interest rates go up, this problem is going to get worse." Goldser's Minnesota 2020 colleagues have done the math. Assuming Ms. Average Graduate takes 10 years to pay back her loans, the change that went into effect July 1 would cost her $11,352 in interest, vs. $6,294 if Congress had extended the pre-July 1 rate a year or two. Wait, you're saying to yourself, you just did that math on all loans, not just the subsidized Staffords that got a new rate. You're right — this is where it starts to get mondo confusing. The proposed fixes would affect all government student loans, and some of them would be even more expensive to borrowers. Politicians currently set the ratesRight now, politicians set the rates at which students and families borrow. President Barack Obama and U.S. Rep. John Kline, the Lakeville Republican who chairs the powerful House Committee on Education and the Workforce, both want interest rates to go up and down with the market. But their proposals differ greatly. Both proposals would peg interest rates to the Treasury rate, the interest the government pays investors who buy its debt. The rates go up and down depending on the market and on how long the investments last. Kline's Smarter Solutions for Students Act, which passed the House in May and which Obama has threatened to veto, would have created variable interest rates for all loans, pegging both kinds of Staffords to the 10-year Treasury bill plus 2.5 percent. Right now, that would make the interest on those loans 4.7 percent. But the Congressional Budget Office foresees rising rates, which means that within five years they could reach a proposed cap of 8.5 percent. At that point, this year's 6.8 percent would start to look like a bargain. Just to inject a little more uncertainty, under this GOP proposal the interest rate would fluctuate during the life of the loan. So you might start school with a rate of 4.7 and end up paying nearly twice that. Obama's approachBy contrast, Obama would keep interest rates fixed during the life of the loan, and would not cap them. He would peg subsidized Staffords at the 10-year Treasury rate plus 0.93 percent and the unsubsidized Stafford at the 10-year rate plus 2.93 percent. The PLUS loans available to parents and grad students would become more expensive under both plans, too, in essentially proportional rates. The other five proposals? We'll spare you the fine print, Indebted, which involve things like using the 90-day Treasury bill instead of the 10-year, except to note that another member of the Minnesota delegation, Minneapolis DFLer Keith Ellison, backed an idea advanced by Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren. You can't lie to Warren about things like debt and T-bills. Her plan would have made the loans darn near free by pegging them to the rock bottom federal discount rate. So naturally it died before it got out of the gate. You're sounding awfully cynical. Almost like you think they're making this too complicated for most people to understand on purpose. Do you think they're trying to hide a profit motive or something? — Doubtful about all this Indebtedness What you likely consider an unbearable yoke of indebtedness the financial services industry refers to as a "loan product." A loan product many of your compatriots will use to attend an institution that must please not just members of the academy but shareholders. And there's some truth to the notion that easy student credit doesn't create many incentives for nonprofit and public universities to take a hard look at costs and at runaway tuition increases. So it shouldn't surprise you that they're not all for-profits. Although Kline is the far and away winner in this story, Democrats and Republicans alike have received donations from and been lobbied by the financial services industry and education sector. Good luck finding a federal-level elected official who can't be tied to the debate in that way. The for-profitsBefore we part, let's circle — briefly and cynically — back to the start of our chat. According to the state study mentioned up top, the highest student debt loads in Minnesota were acquired by students at the Art Institutes International, at $36,000 and $55,000 for two- and four-year degrees — many of them in low-paying "passion" fields such as cooking. The Art Institutes are owned by the publicly traded Education Management Corp., the nation's second-largest owner of for-profit institutions of higher ed with 110 schools in 32 states and Canada. It gave $10,500 to Kline in the 2012 election cycle — a drop in the bucket. If that doesn't surprise you, consider this: Goldman Sachs owns 40 percent of Education Management. Goldman Sachs makes student loans and buys and sells securities that — shades of the mortgage bubble bursting — are made up of student loans. And so as you are contemplating the loan product that may or may not get you the degree that's your ticket to a prosperous future, know this: The entire juggernaut can't survive without students, Doubtful. Profit makes this particular republic go round, so there are all kinds of folks willing to lobby to keep the fiscal taps on. | ||||||||||||||||||

| No Barriers program helps decrease <b>student loans</b> by more than half <b>...</b> Posted: 21 Sep 2015 01:07 PM PDT In a sign of the impact from recent efforts to enhance affordability for students attending the College, the number of first-year students at the University of Chicago who took out loans to help cover educational expenses has decreased by more than half this year. The steep decrease in borrowing is a direct result of the University's No Barriers program, which launched in October 2014 and eliminated the student loan requirement from undergraduate, need-based financial aid packages. The University replaced those loans with direct grants. "We knew the No Barriers program would address a real need among students, but the dramatic effect in a short time frame is even beyond our hopes," said John W. Boyer, dean of the College. "This means many more of our students can focus on their intellectual lives and personal and career development without having to worry about debt after they graduate. It's deeply meaningful for them and for the College community as a whole." UChicago Admissions officers have been educating families about the admissions process and the No Barriers program, finding that parents are very interested in the assistance UChicago offers. More than 100 free information sessions nationwide on the college application and financial aid process have been presented, bringing guidance on how to apply to any selective college to more high school students than ever before. The sessions will continue this fall, with several bilingual English/Spanish sessions, increasing the total number of sessions during the first year of No Barriers to an anticipated 150. No Barriers' commitment to a no-loan policy for all financial aid recipients has its roots in the 2008 inception of the Odyssey Scholarships program, a pioneering effort to reduce or eliminate loans for students from families with limited incomes. The Odyssey Scholarships were launched with a $100 million donation from an anonymous alumnus and have continued through the generosity of thousands of alumni, parents, families, and friends who have contributed to the fund. Odyssey continues to bolster aid and programming for low-income students through increased financial support, career guidance, personal mentorship and community support. Those benefits were extended to students from Chicago high schools in 2012 with the creation of UChicago Promise, a program that also offers application workshops for students and high school counselors, and mentoring programs to help students apply to the colleges of their choice. Increasing support for student financial aid is a major priority of the University's ongoing $4.5 billion fundraising effort, the University of Chicago Campaign: Inquiry and Impact. To date, the College has raised about $81 million toward its Campaign Financial Aid goal of $150 million. Financial Aid is the highest of the College's Campaign goals, followed by Leadership and Community at $114 million and Academic Programs and Research at $105 million. No Barriers is a comprehensive initiative designed to eliminate obstacles that students face when applying to college. It supports students in receiving an empowering education, ensures that students can leave college without the burden of debt, and offers robust, personalized support that gives every UChicago student, regardless of background, opportunities to discover their passions and take full advantage of a world-class education from the College. | ||||||||||||||||||

| We Have a Massive <b>Student Loan</b> Forgiveness Program—Why Is It <b>...</b> Posted: 07 Sep 2015 12:00 AM PDT When Camille Schenkkan had to take out thousands of dollars in student loans to pay for Claremont School of Management's graduate program, she told herself not to worry. She had learned from colleagues also entering the field of arts education about a U.S. government program that would reward her if she spent 10 years making loan payments while working in a nonprofit. Which was exactly the field she wanted to enter anyway. The reward? A large chunk of her student loans would be forgiven as part of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (PSLF). PSLF is not the first forgiveness or assistance program for public servants. Smaller state, federal, local, and university programs have used loan assistance to effectively encourage students to become teachers and public-sector doctors, nurses, and lawyers, often for less pay than in the private sector. But the PSLF program is by far the largest experiment of its kind—both in the scope and scale of its forgiveness. With 25 percent of the nation working in "public service" as the program defines it and some 70 percent of graduates leaving college with student debt—now averaging more than $30,000—millions stand to profit from the PSLF program's cancellation of debt. For Schenkkan, the promise of forgiveness allows her to pursue her passion and offers an early escape from crushing student debt. "It was a carrot of a way you could actually do this," she said. But the program's virtues get lost in byzantine complexity. In order to qualify for its reward, borrowers have to navigate a series of uncoordinated and often unresponsive Kafkaesque bureaucracies, making the program's promise of forgiveness appear less like a panacea and more like a question mark. The PSLF program was created in 2007, during the twilight years of the Bush Administration, as part of the College Cost Reduction and Access Act (CCRAA). Previous piecemeal efforts at forgiveness programs weren't fulfilling a broad enough goal: to encourage people to choose positions in public service and to help them keep those jobs long-term. Panics over predicted labor shortages in hospitals, public schools, and public defenders' offices indicated to lawmakers that a broader-based program to maintain this critical work was needed. Enter the bipartisan and ambitious CCRAA, widely described at the time as "the single largest investment in higher education since the GI Bill." The way it works, in theory, is straightforward:

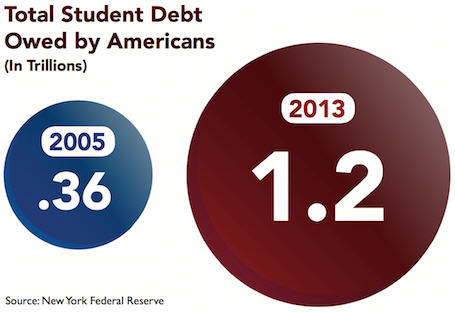

In other words, 10 years of public work and qualifying payments mean that the thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, of dollars hanging over your head like Damocles' sword will disappear, once and for all. Considering that many jobs in the public sector require graduate degrees, the effects could be enormous. PSLF might even help to defuse the time bomb of national student debt, which now totals more than $1.3 trillion. But in practice, every step of PSLF's process has been extremely confusing—not least because the federal government planned none of them in advance. Many of the required provisions of the program did not exist until years after it was technically underway. Two of the qualifying repayment plans for PSLF—IBR and Pay As You Earn (PAYE)—took effect in 2009 and 2012, respectively. No "Dear Borrower" letter laying out the specifications of the program existed until 2011. Borrowers could not find out if their employment formally qualified and what counted as full time, as part time, or as a proper nonprofit—and therefore, how many qualifying payments they had made—until 2012, when the employment certification form was first introduced.

Student loan lawyers and advocates (many of them borrowers themselves) say that the opaque process, and lack of assistance offered, leads some people to give up. "They don't make it easy," said Claire Crowley, a student loan lawyer. "Which is also one of the reasons that people go into default."Angela Mrozinski, who has been making payments toward forgiveness for four years, has found the touch-and-go development of such an extensive program disconcerting. "It seemed so odd to me that they have this large program, but they are trying to formalize it as they go," she said. In 2011, Schenkkan consolidated her federal loans, chose a payment plan, and began making payments toward forgiveness. But in spring 2012, she received a letter informing her that she had made zero qualifying payments, despite the fact that she had been paying for more than 12 months. After many phone calls, she discovered she was on the wrong version of the standard repayment plan: The standard 10-year repayment plan qualified for PSLF, but her 25-year repayment plan, then also called a standard plan, didn't, despite the fact that there would be nothing left to forgive at the end of a 10-year repayment plan. The Department of Education's website at the time did not clarify this distinction, she said. Schenkkan is hardly the only borrower to have missed this difference. Her friend Neal Spinler, who thought he had been paying toward PSLF for two years, made the same error. Many others have made months, sometimes years, of payments only to discover that none of them qualified. Their experience drives home what longtime student loan lawyer and advocate Heather Jarvis calls the "convoluted complexity" of the entire system. Schenkkan previously worked as a grant writer and considers herself financially literate, but as Jarvis explained, "It doesn't matter how long you spend on your research and how sophisticated you are because it's incredibly hard to navigate even when you have accurate information." In the decade-plus journey toward forgiveness, borrowers have no way of knowing whether their applications will be accepted. Adding to this uncertainty: The last and most important step of the program is still under construction. The application form for forgiveness does not yet exist. The Department of Education has stated that forms will be available closer to the first eligible date, in 2017. Spinler didn't think he would finish paying off his student loans before he was 60, but if all goes according to plan, even in spite of his two lost years, he will qualify for forgiveness in 2022, when he's 47. Assuming that a quarter of the roughly four million borrowers on a qualifying plan who stand to benefit from the program are public servants, about a million people like Spinler potentially qualify for the program each year. But exact numbers on program participants are impossible to find—because they don't exist.

That's because the program isn't quite a program yet. Even when borrowers obtain correct information about PSLF and take steps to become eligible, they are technically not accepted into the program until after they have made all 120 qualifying payments and applied. This means that the earliest anyone would be eligible to actually enter the forgiveness program is 2017. The Department of Education has no way of keeping count because borrowers may not have voluntarily submitted their most recent employment certification forms. According to a Department of Education spokesperson, nearly 360,000 unique employer certification forms have been submitted as of May 2015. There is no strict requirement that borrowers complete any of the forms until they apply for forgiveness, at which point they are expected to assemble a decade's worth of documentation as proof. The stakes are high—and not just for the government. Mrozinski, Schenkkan, and Spinler, among many others, report experiencing doubt, uncertainty, and severe stress throughout the process. Each discussed how the requirements of the PSLF program, along with the usual burden of student loans, affected their search for jobs, working schedules, and family planning. "You have to make very important decisions that have far-reaching financial implications to take advantage of the benefits," said Jarvis, "like considering whether to postpone and delay children." Jarvis added that the stress borrowers feel is understandable. "They're pioneers in the program, and they don't have any history, experience, or precedent to rely upon." Borrowers are concerned about President Obama's twice-floated budget proposal to cap the amount forgiven by the program at $57,000, which would limit the program's benefits for those who need them most. More than one in four public defenders surveyed by the National Legal Aid and Defender Association have in excess of $175,000 in student loan debt, and over half said they would leave the public sector if the program were capped. Legislators have also toyed with the idea of eliminating the program entirely, but all four student loan lawyers interviewed stated that a total termination of the program is not only extremely unlikely but would also not affect those who've already taken out loans. But the program's "all-or-nothing" benefits are perhaps the most terrifying part. "If it all works out, my loans will be forgiven, and it will be amazing, and I'm really sort of counting on that," Mrozinski said. "But once people hit this 10-year mark and the government starts to forgive these loans, where is this money going to come from? Are they actually going to support it once they put their money where their mouth is? "If what I'm doing doesn't qualify for forgiveness," she added, "then I'm screwing myself right now."

Any reform to PSLF has the potential for huge effects—for better or for worse. What's clear is that for the program to be as powerful as it intends, more transparency and simplicity is needed. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) estimates that about one in four workers in the United States qualifies for PSLF, but it's unknown how many qualify yet fail to take advantage of the program. The complexity of program requirements and confusion of program options, the CFPB stated, may act as a "deterrent for borrowers weighing a career in public service." Jarvis says that the program's benefits are not as effective as they could be had the program been "simplified and easier to access." The Student Aid Bill of Rights, to be implemented within the next year, should streamline some aspects of the process for borrowers. There have been some efforts on the part of the Department of Education to promote the program's existence to the millions who might be eligible: a revised website, the introduction of necessary forms, and a more simplified and streamlined presentation of the necessary information. According to a Department of Education spokesperson, the Federal Student Aid office, which oversees PSLF, will be planning its first direct outreach campaign about the program to borrowers later in 2015. To help employers provide information about loan forgiveness programs to their employees, the CFPB issued a toolkit and asked public service employers to contact them to take a "Public Service Pledge." But student advocates, including Jarvis, have said that until the government and contracted loan servicers are also mandated to provide their clients with full information about available programs, and until outreach efforts become formalized, PSLF's crucial benefits will remain unsung. In the coming months, the CFPB will release the results of its investigation of servicers failing to provide information or providing misleading information. For now, the program's potential beneficiaries can only hope. Schenkkan always educates the intern program she runs all about PSLF and how exciting it is. "But a part of me is worried that it will go away," she said. "It still seems too good to be true." If all goes to plan, billions of dollars in student loans will annually disappear. It's no rolling jubilee, but it's a giant leap for studentkind. Resources to help you navigate the PSLF program: yesmagazine.org/PSLFhelp | ||||||||||||||||||

| The <b>student loan</b> crisis hurts for-profit and community college <b>...</b> Posted: 12 Sep 2015 07:00 AM PDT

The Brookings Institute, a DC-based think tank, published a paper in September that examined the types of borrowers most prone to default and delinquencies on loans, and presented some surprising findings. The student loan crisis is actually a "selective" crisis, according to Brookings. Students who attend for-profit or community colleges are much more likely to default on their debts than other graduates. "Half of borrowers exiting school in 2011 attended a for-profit school or a 2-year college," the paper noted. "These borrowers represented 70% of defaults." That is a relatively new phenomenon, as the makeup of student loan borrowers has changed drastically since 2000. You can see in the chart below that a significant number of the colleges in America whose students owe the most in 2014 come from for-profit schools.

The paper continues on to explain that students from for-profit and community colleges have higher numbers of defaults and delinquencies, because they are less likely to complete their degree programs, have higher levels of unemployment, and normally earn less than students who attend 4-year colleges and graduate programs. These factors were further exacerbated by the economic downturn. Brookings, however, does have some positive news for student borrowers. The paper predicts that delinquency is set to decrease as the economy continues to improve and there are more job opportunities. Additionally, as oversight over for-profits strengthens, there will be less opportunity for abusive tactics. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from student loan - Google Blog Search. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |